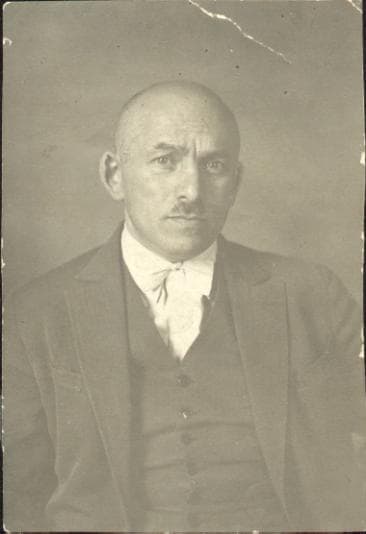

Nina’s Grandfather

BORIS SHTERNBERG

(April 14, 1886 — Dec. 19, 1937)

Boris Shternberg was born to a poor Jewish family in Lutsk (Volynskaya guberniia). His mother, Matilda, ran an eatery for students. When he was about 10 yrs. old (c. 1895), he and his parents emigrated to America, together with his younger brother and sisters.

He attended elementary school in Chicago for several years, until his father, Akim, decided to take the family back to Lutsk. Back in Lutsk, Boris was not admitted to the gymnasium because of a ratio system that limited the number of Jewish students. He went to Warsaw to study at a secondary school. Upon graduation he became a student at a commerce college in Kiev. In 1905 he became a member of the left wing of the Bund*, an organization whose goal was Jewish cultural autonomy. During his fourth year of studies he was expelled from the college because of his political activities.

At the beginning of WWI he enlisted in the Russian army as a “volnoopredeliaiushiysia” (volunteer) and was awarded the St.George Cross for bravery in battle. In 1917, impressed by the ideal of Communism promulgated in the army by A. Troyanovsky (later, a Soviet ambassador to Japan, and later still, ambassador to the US), he became an advocate of Russia’s withdrawal from the war. He persuaded many soldiers to lay down their arms. In 1918 he became a member of the Russian Communist Party.

In 1920, when Soviet rule was established in the Ukraine, he was appointed deputy minister (narkom: narodnyi komissar) of RKI (Raboche-Krest’yanskaya Inspektsiia)in the Ukraine. At that time Stalin was the head of RKI in Moscow, and Boris Shternberg disagreed with him on a number of issues. As a result of these disagreements, Shternberg was transferred to work in Ekaterinburg, which at that time was considered a demotion.

In 1924 he became a member of the governing board of Gostorg (literally: Government Trade Organization) in Moscow. In 1927 he was elected a representative to the Moscow Soviet (the Mossovet, i.e. Moscow City Council). Subsequently he was a member of the Presidium of Moscow Soviet, deputy president of the Moscow Soviet, and head of administration of the Moscow water supply. At one time or another he was responsible for each of the city’s utilities, including electricity, gas, and water.

During those years he was constantly under threat from party purges. He was often told that his past membership in the Bund would be held against him. At that time most people were not aware of the difference between the Bund’s left wing, which Shternberg had belonged to and which was allied with Communism, and its right wing.

In the summer of 1937 the daily “Evening Moscow” featured a long article which accused almost all members of the Moscow Soviet Presidium of using their high rank for personal gain. The only member whose name wasn’t mentioned in the article was Boris Shternberg. In fact, not only did he never use his power for personal gain, he did not even take a vacation for seven years.

On October 17th 1937 he was arrested at his home, in the middle of the night, and accused of masterminding a counter-revolutionary plot. He was held first in the Butyrki jail, then in Lefortovo. He was sentenced to ‘ten years in distant camps without the right to correspondence,’ a euphemism for a death sentence. Every day his wife and his 17-year-old daughter stood at the prison entrance, in the long lines of family members of those similarly accused, with parcels of money for him. If jail officials accepted the money (allegedly on behalf of the prisoner), it meant that the prisoner was still alive. On December 20th their parcel was turned down: Boris Shternberg had been executed the day before. A month later, on January 20th 1938, his wife, Yevgeniya Yakovlevna Shternberg (nee Kokel), a microbiologist who had nothing whatsoever to do with politics, was arrested as “a member of an enemy’s family” and condemned to five years in a concentration camp (officially called “corrective” hard labor camp).

In 1956 Boris Shternberg was rehabilitated “for the absence of content of crime”. In the middle of the 1990s, when it became possible to see his file at KGB headquarters in Moscow, family members read that he had been accused of “poisoning Moscow’s water supply” and “participating in a subversive Trotskyist organization.” An innocent man, an idealist who always believed he was helping to build a better world, he was one of twenty million victims of Stalin’s Great Terror.

Yevgeniya Yakovlevna, Boris Shternberg’s widow, spent five years at the Temnikovskii concentration camp in Mordovia. She was released in January 1943 at the end of her term and, because of her poor health–caused by the conditions in the camp–was allowed to leave Mordovia. Her daughter, Maya, was at that time living in Kzyl-Orda, a town in Kazakhstan, and working as a nurse in a clinic for wounded soldiers. (She had been evacuated from Moscow in October 1941, when the Germans were close and expected to occupy the city.) Yevgeniya Yakovlevna joined her there. When the war ended, her daughter went back to Moscow, but Yevgeniya Yakovlevna was forbidden to live in Moscow as she was still considered “a member of an enemy’s family”. She rented a small room in Laptevo, a town near Moscow, and she worked at a clinical laboratory which she had set up at a local hospital. After Boris Shternberg was posthumously rehabilitated in 1956, his widow was finally allowed to move back to Moscow. She died in 1970 at the age of 82.

*FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE BUND AND ITS HISTORY, GO TO

http://www.iisg.nl/collections/yiddish/yidhis.html

http://www-hoover.stanford.edu/hila/judaica3.htm

FOR INFORMATION ABOUT THE GREAT TERROR AND THE SOVIET CONCENTRATION CAMPS:

http://www.osa.ceu.hu/gulag/ (archival photos of GULAG)

http://www.cdi.org/russia/230-2.cfm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Purge

The Great Terror by Robert Conquest)

Koba the Dread: Laughter and the Twenty Million by Martin Amis